When I was a student at University I had a habit of working long hours in pursuit of high grades. While some of my peers collaborated on assignments or accepted average grades, I took a different approach where I reduced the number of classes that I took so I could spend extra time on each course and achieve top marks on assignments. In the summer time I caught up by taking electives. During one year of my studies I would regularly work until I had no clean clothes left, no food in my fridge and I was completely exhausted. This was about a 10-14 day cycle, 9-13 days of work followed by 1 day of shopping, cleaning and sleeping. I got As in all my classes that year but was totally burnt out at the end.

Dennis, our group leader, told a similar story about being a crane operator at a steel mill, going into work, and being furious with what he saw as the mess in the yard left by the other guys on the previous shift. He would meticulously reorganize everything in a way that he thought was ideal only to return to work the next day to find yet another mess left by what he called his lazy and unprofessional co-workers. He complained loudly to his supervisor about this, and spent a great deal of time being angry at the other employees and hating his job.

Depending on where you work and whether you are a student, steelworker, restaurant worker, hospital worker or homemaker / family caregiver, you may be struggling with the idea that your work output should be as high as possible. This can lead to anger, frustration, burnout, loss of sleep, and serious mental health issues. If you feel that way I'd like to point out several interesting articles.

Bring back the 40-hour work week is an article published by Salon in 2012 that summarizes the last 120 years of research on the idea of the 40 hour work week, its history, and where it came from. Many of us are aware that in the 1800s when factory work began days were 12 hours long, holidays were a rare thing and pay was low. In the early 1900s trade unions sprang up and I always thought that it was these unions that fought for reasonable work weeks.

While it is true that unions fought for reasonable working hours the Salon article points out that the 40 hour factory work week originates with Henry Ford. We all think of Ford as the first to use the assembly line but as part of inventing modern mass production he also experimented socially with various approaches to the work day. Ford found that the 40 hour week was a sweet spot in terms of optimizing worker output. If workers were on site less than 40 hours per week they tended to lose touch with what was going on. If workers were on site for more than 40 hours they tended to make mistakes and either produced faulty products or hurt themselves. For workers to be efficient and reliable the best strategy was to give them a reasonable pay, consistent weekly hours, and send them home after five days of work to rest and forget about their jobs.

This same research was repeated again and again throughout the 1900s, although in the last 30 years this idea has been lost. Especially in the computing industry we see managers advertise for programmers with "passion" for computing and "dedication" to customers. Last year I was assigned to work under a new manager who talked this way and I quickly learned that these were code words for overtime hours and work from home on the weekend. I work in a salaried environment with no union protection or way to claim overtime so when my new boss suggested that 60 hours per week was really preferred and what employees needed to do to get bonuses this came across as a genuine threat to my livelihood and sanity. Happily I no longer work for this person however the experience was unnerving and for me as a recovering nervous patient this amounted to a serious set back for my mental health.

One of my coworkers previously worked in the game industry where, much like the movie industry, there is an ongoing expectation that you will sacrifice everything for your job. Often young workers are lured in with the idea that movies and games are fun and cool, that it is a privilege to have a job where you get to "play" all day and that you should be willing to sacrifice all of your life to this endeavour. Managers in computing might agree that a 60-80 hour work week is dangerous for factory or construction workers since there are real hazards in operating heavy machinery, but that these same problems don't exist in a white collar environment.

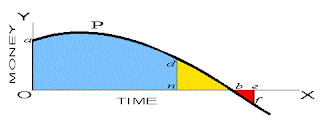

Why Crunch Modes Don't Work: Six Lessons is another interesting article that focuses on the game industry and provides the following graph that summarizes the problem:

While in the computing industry people don't generally get hurt by heavy machinery it is possible to write a devilishly complex bug as part of a last minute hack that gets shipped to customers. Those kinds of bugs are written by overworked tired out programmers who are pushing themselves beyond reasonable limits. Bugs of this sort can tank a product and create considerable embarrassment and loss of face for the company. Think about Windows Vista if you remember it, or the last game you played that crashed and destroyed your high score.

Perfectionism is a trap. It is a form of unrealistic thinking where we imagine a simple relationship between hours invested in a project and the quality of that project. We imagine that every hour we work on a project is just as good as any other hour, we imagine that despite being made of flesh and bone we can push ourselves to behave like machines, that we don't need a social life, that our friends and family will be there later on, and that with enough will power we can force ourselves to be perfect so that we can perform flawlessly.

We also believe that a job done to the highest standards will mean happiness and a perfect life. We imagine a polished and organized home, a grade report with As in every class that will lead to scholarships and awards, a promotion each year for work conscientiously done, a boss who appreciates our high standards and the respect of our peers and loved ones for our outstanding efforts. Just a little bit more hell today will lead us to a future where everything is just right. When we aren't happy despite achieving some of these prizes we are surprised and feel let down. When the non-stop treadmill of endless overwork follows us home, keeping us awake until 3am and isolates us from family and friends we slide into a state of dull oblivion only to awake at 8am "ready" for more work. In Mental Health Through Will Training Dr. Low writes:

"This is altogether different in the instance of the perfectionist or the person consumed with the desire to achieve exceptionality. To him every puny endeavor, each trivial enterprise is a challenge to prove and to maintain his exceptional stature. His life is a perennial test of his singularity and distinction. For him there are no trivialities, no routine performances. He is forever on trial, before his own inner seat of judgement, for his excellence and exceptional ability. He cannot achieve poise, relaxation, spontaneity. He cannot afford to have the COURAGE TO MAKE MISTAKES. A mistake might wipe out his pretense of being superior, important, exceptional. With no margin left for mistakes he is perpetually haunted by the fear of making them. The fear paralyzes decision, hampers actions and confounds plans. Striving for indiscriminate peak performance and confronted with his pitiful record of jobs undone, unfinished and hopelessly bungled he is horrified by his cumulative inefficiency and becomes confused."

In Recovery we talk about being average, about not comparing yourself to others but only tracking your improvement by seeing how you are doing better now than you were in the past. We talk about having realistic expectations for yourself and for others, and about having the courage to make mistakes.

Dennis changed his attitudes about his coworkers and stopped complaining to his boss about what he saw at work. For him Recovery provided a life changing alternative where he stopped comparing his efforts to the efforts of his peers and learned to accept that there are many average individuals who just do average work and that this is okay. By changing his attitudes Dennis started to enjoy his job. After changing his behavior he realized that his boss didn't actually want to hear him complain about what was wrong with the other guys at work. Dennis stopped hating his job, reduced his stress at home after work, and improved his relationship with his supervisor.

For me, I've learned to accept that 40 hours of work on a computer is really all I can do in a week. I limit my time at work to 8-9 hours per day, I take at least a 30-45 minute break each day where I leave the building and I only work on weekends when something unusual comes up. I no longer pursue promotions or awards and I'm quite happy being an average worker. I've found that not everyone shares my ideas about limiting work hours and I don't discuss the subject with too many people. While I still compare myself to others, and this isn't ideal, I try to improve my attitudes by being focused on my own tasks. I take some comfort in the knowledge that my 40 hour work week allows me to be productive and happy, and that my old boss who lives alone and has sacrificed everything for a career likely isn't any more productive than I am.

If you are suffering from feeling the need to be perfect or have sacrificed it all for work, you can come and talk to us about it during meetings and learn some of the techniques that we suggest.

More Information

A Place Beyond Procrastination

About Recovery Hamilton