While anxiety can be a general experience that drags us down on a day to day basis, fear in the moment can be quite intense. Fear usually has an immediate stimulus. With fear, we see a snake and become apprehensive or we look down from a tall building with unease. Anxiety in contrast can arise without any physical stimulus, sometimes remembering a painful past event or thinking about something in the future that we'd rather avoid can lead to anxious feelings. There is a natural feedback loop that occurs between fear and anxiety. A shock in the moment creates an impression, one that we don't want to experience again, so we worry, and spend time planning to avoid an imagined unpleasant future event. If we spend a lot of time ruminating on fearful experiences our general levels of anxiety may creep upwards. Sometimes fearful thoughts become intrusive and can invade our experience seemingly out of our control. Anxiety driven by rumination and fearful experiences can turn into a painful vicious cycle that takes on a life of its own.

There is a part of our thinking that we can direct, and there is another part that seems to arise on its own. Even those of us who struggle with mental health issues have a strong measure of control over most of our own thoughts. We can plan, decide, make choices, and solve complex problems with varying degrees of effort. In contrast, some ideas arise spontaneously without our bidding; dreams, imagination and inspiration all fall into this category and are positive examples of spontaneous thoughts. The same sort of processes may also be at work with our fears. Some fears are rational and based on deduction and reason. While its troublesome to pay my taxes I know that I should because the consequences of not doing so can be unpleasant, and essentially, I fear those consequences. I don't do my taxes for love of the government, but more for fear of what will happen if I don't. I also have irrational fears, for example, when the phone rings my first instinct is to not answer it because I imagine that whoever is calling wants something from me and is going to make accusations and burn up a lot of my patience and time.

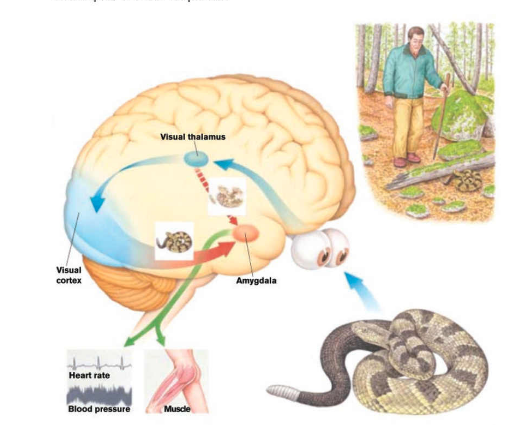

How is it that our thought processes become split? Do only some people feel this way? How can we be in conflict with ourselves? Joseph E. LeDoux described a fear response that is based on two pathways within the brain. LeDoux is an American neuroscientist whose research is primarily focused on the biological underpinnings of emotion and memory, especially brain mechanisms related to fear and anxiety. LeDoux studied fear using a simple behavioral model based on Pavlovian fear conditioning in rodents. This procedure allowed him to follow the flow of information resulting from a stimulus through the brain as it comes to control behavioral responses by way of sensory pathways. LeDoux identified two sensory roads to the amygdala (the memory and emotional center), with the “low road” being a quick and dirty subcortical pathway for rapid activation of behavioral responses to threats and the “high road” providing slower but highly processed cortical information. His work has shed light on how the brain detects and responds to threats, and how memories about such experiences are formed and stored through cellular, synaptic and molecular changes in the amygdala. LeDoux’s work on the amygdala's processing of threats has helped us to understand exaggerated responses characterized by anxiety disorders in humans. Studies in the 1990s showed that the medial prefrontal cortex (rational thinking part of the brain) is able to stop the threat response and paved the way for understanding how exposure therapy reduces threat reactions in people with anxiety by way of interactions between the medial prefrontal cortex and the amygdala.

|

LeDoux Fear Response From "Abnormal Psychology" by W.J. Ray

|

The LeDoux fear response is made up of two pathways for the processing of fear. One pathway is fast and outside of awareness, while the other is slower and has a conscious component. In the previous figure, visual stiumuli (a snake) are first processed by the thalamus which passes rough, almost archetypal information directly to the amygdala. This quick transmission allows the brain to respond to the possible danger by raising the respiration and heart rate and creating tension in the muscles so we are ready to act. Meanwhile the visual cortex also receives information from the thalamus and, with more perceptual sophistication and more time our mind can process the actual threat level and develop a clearer understanding of what is going on. This allows us to either dismiss the stimulus as not a real threat, or we can develop a plan of action more sophisticated than jumping out of danger's path. We have a sense of conscious control over this second pathway, and while our "jump" response may have already been triggered, with some thought we can choose a more comprehensive sequence of steps to deal with the situation.

While our initial reaction may be incorrect, there is an evolutionary advantage to being prepared for danger as soon as possible. We always have the second opportunity to consider in more detail whether the threat is actual or not. However, for some of us our initial response has become too sensitive. We feel always on alert, and we have begun to believe our intuitive response and accept it without considering it carefully. If we always believe this initial response we aren't using our rational facilities to reconsider what is going on and we are only seeing a portion of the picture. Can we then simply anticipate this response and crush down our irrational or instinctive nature? Given the absence of conscious control over this process the answer is no. Our initial response is determined by past experience, instinct, and other difficult to control aspects of our mind. So what can we do?

In the chapter titled "Intuitive Versus Discursive Thought in Temper" from MHTWT Abraham describes a dual response and argues that we have very little control over the initial response, but we need to be aware that we can exert a measure of control over the secondary response and that it is in this secondary response where we have the opportunity to change our experience.

E: ... a temperamental outburst runs in stages. First, you explode and go into a rage. In a given instance, you may rave on for two or five minutes. During this time you are "out of your senses" and will not be likely to exercise a great deal of thought. You will certainly not stop to consult your memory recalling what I told you about control of temper. So I take it that during this initial stage of your explosion you will not think of the instruction I gave you. You will simply rave on until your anger will subside. I shall call this initial stage of your temper the "immediate effect of the temper outburst." I hope you realize that when I want you to practice avoiding intuitive conclusions, I do not ask you to do that during this stage of the immediate effect. But after the immediate effect is over, you enter a "cooling off" process which may last some ten or fifteen minutes. This is the temperamental after-effect. Once the after-effect sets in you begin to think, perhaps not very clearly, but sufficiently so to be able to remember what I told you. Whatever thinking you do during the immediate effect is intuitive, vague and dim. But in the after-effect your thought becomes discursive again. You can then reflect and meditate. The question is whether your type of reflection will be rational or emotional. If it is emotional you will continue to fume, will brood over the outrage of which you were the "innocent victim." Burning with righteous indignation, you will justify the explosion which you released during the immediate effect and will give it your endorsement. Once you endorse your outburst as justified, you are primed for another explosion; you fairly itch to pay that fellow back" and thus keep your temper boiling in anticipation of another bout. This is the last stage of the uncontrolled temperamental cycle which we shall call the stage of anticipation. It is called the stage of anticipation because in this third phase of the temper outburst you anticipate a renewed squabble in which you expect to come out on top. You anticipate a victory which will wipe out the "disgrace" of the present defeat. You will understand now that the so called temperamental cycle if left to itself without an attempt to control it consists of three discrete stages; (1) the immediate effect, (2) the after-effect, (3) the anticipation of a renewed outburst. Can you tell me now which stage of this cycle you must make use of for the purpose of remembering what I told you in matters of control?

P: You said it can't be done in the immediate effect. So I think it will have to be done after that.

E: That's correct. You will have to make use of the aftereffect. Of course, I do not expect you to succeed the first time, nor do I expect full success the fourth, fifth and sixth time. Instead, I presume you will become emotional in the first few beginnings of your practice and your after-effects will be spent in spells of fussing and fretting, with the result that the temperamental cycle will be run unchecked through its immediate effect, after-effect and the anticipation of the next temperamental "comeback." I hope, however, that after repeated practice you will finally manage to stop short at the end of the immediate effect and that henceforth the after-effect will be given over to a sane, rational appraisal of the situation in which you will refrain from endorsing your explosion, thus avoiding the anticipation of and preparation for the next outburst. This will come to pass if, after a few initial failures, you will not permit yourself to be discouraged and will continue practicing with solid determination. You will do that if you have the genuine will to remedy and check your temperamental habits.

I found reading about LeDoux's investigation in to the dual pathway to be quite interesting. Abraham Low's description of the stages of a temperamental response to a situation is mirrored by LeDoux's experimental biology. Learning to manage your feelings isn't necessarily about gaining complete control over them, or having the ability to squash unpleasant feelings whenever they arise. Within our brains the biology dictates that a portion of our emotional response will be instantaneous and automatic, so we will never be able to fully control every thought that we have. The goal is to recognize that while we can't control this immediate reaction, we can recognize it, and we don't need to let this intuitive response dictate our whole response.

In Recovery meetings we always acknowledge that you are "entitled to your initial response", we recognize that for everyone the immediate onset of a conflict, surprise, or upsetting situation is intuitive and outside of our rational control. All we need to do is observe the reaction and be aware of it and accept that while it may be reasonable there is also a good chance that it may not be reasonable. After the initial response you have the chance to work on it and this is the point where we can apply tools. In meetings participants practice this exercise by describing in a concisely reported fashion, first their initial response to a difficult situation, then their conscious efforts to understand and manage their responses. This formula allows us to learn new automatic responses over time, we effectively are changing our past conditioning. After successive attempts to understand our initial response and decide which parts must be addressed and which parts must be ignored we can reduce our tendency to see troubling situations as emergencies, and we can take the time to accept and understand our own reactions as average.

More Information

The Physical Response to a Fight or Flight Impulse

The Biology of Depressions Vicious Cycle

Feelings are Not Facts